paperback, 408 pages

Published May 1, 2010 by Kersplebedeb, Kersplebedeb Publishing.

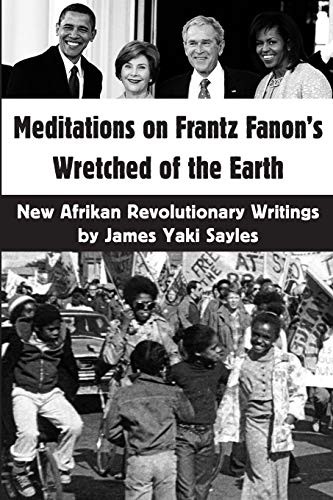

New Afrikan Revolutionary Writings

paperback, 408 pages

Published May 1, 2010 by Kersplebedeb, Kersplebedeb Publishing.

Like the revs that he most considered his teachers—Malcolm X and George Jackson—James Yaki Sayles grew up poor and found his maturity in prison, the place that Malcolm called “the Black man’s university.”

A child of Chicago’s South Side streets, Yaki always just thought of himself as a blood, “just another nigger doing a bit” (to borrow the laconic words of one of the Pontiac state prison revolt defendants). And it was in the prison movement that he found his place in the battlefield. Although he made revolutionary theory his work, his life was rooted in a time of urban guerrillas and the armed struggle. Which makes his writing much more difficult to read, but with a warning of danger and commitment that is so often missing in these neo-colonized times between the storms…

Yaki soon became a leading activist in the small prison collectives in his state. First in …

Like the revs that he most considered his teachers—Malcolm X and George Jackson—James Yaki Sayles grew up poor and found his maturity in prison, the place that Malcolm called “the Black man’s university.”

A child of Chicago’s South Side streets, Yaki always just thought of himself as a blood, “just another nigger doing a bit” (to borrow the laconic words of one of the Pontiac state prison revolt defendants). And it was in the prison movement that he found his place in the battlefield. Although he made revolutionary theory his work, his life was rooted in a time of urban guerrillas and the armed struggle. Which makes his writing much more difficult to read, but with a warning of danger and commitment that is so often missing in these neo-colonized times between the storms…

Yaki soon became a leading activist in the small prison collectives in his state. First in the Stateville Prisoners Organization, which quickly grew into the New Afrikan Prisoners Organization. There were groups in Stateville, Pontiac, and Menard prisons, as well as individual members in other prisons outside Illinois and rads on the street. Yaki also became an influence in less public organizations.

One thing he never became was well-known. There were definite reasons for this. In part, because Yaki was a very private person who rarely talked about his inner life or childhood, and who never wanted to write about his own past to a curious public. Becoming a radical celebrity was not anywhere in his plans.

Yaki was also unknown because of the role he chose for himself. Much of his writings were not for the public, or even the community as a whole. Most of them were cadre teachings. Typically, Yaki wrote and spoke as a teacher for those already New Afrikan revolutionaries who were cadre. Those who had accepted the responsibility of being organizers and local teachers themselves. Although he was often repeating or underscoring basic political lessons, sometimes these were almost technical discussions. Craft discussions. In the same way that young Five-percenters proudly talk about, “i can do the math,” “i know the numbers.” And as such his words weren’t meant to be entertaining, and rads often complained of finding them as hard to read as some textbook. Far from easy reading. But it’s like, if you wanted to be able to design the flow of water through a hydoelectric plant or do brain surgery on an infant, at the very start you’d be cracking the books late into the night and studying for all you were worth. Yaki didn’t think that trying to transform society was any easier…

When Yaki started out in prison, he had amassed a real library of political and history books, together with magazines and files of documents and correspondence. And he spent hours and hours studying and writing. This gradually became more and more choked off by prison authorities. As he put it: “Inside it only grows worse, not better. Because they keep changing wardens, and every warden has to prove that they’ve made some change or new shit they can point to. Which is only more restrictions.”

By the start of the 21st century, he was limited to one thin cardboard case, only a few inches high, which had to hold any books, magazines, newspapers, notebooks, files, letters, blank paper, pencil and pens he had in his cell. And he had to work mandatory eight-hour shifts every day at the usual makework prison jobs (such as counting out and counting in the checkers pieces in the day room), which cut down on his intellectual hours. All this led him to decide to center himself on one major project which only required two books, a reappraisal and explanation of Frantz Fanon’s great revolutionary writing, Wretched of the Earth…

Here, Yaki is on a mission. To make up for the misunderstanding of Fanon’s politics that he and so many of his young rebel comrades once had. To help guide the study by newer rebels of this complex and difficult reading.