Paperback, 262 pages

English language

Published Feb. 1, 1964 by University of California Press.

Paperback, 262 pages

English language

Published Feb. 1, 1964 by University of California Press.

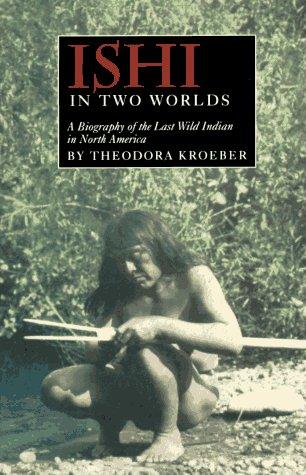

Naiomi Alderman described the book as follows in the Guardian Newspaper; "On 29 August 1911, a 50-year-old man, a member of the Yahi group of the Native American Yana people, walked out of the forest near Oroville, California, and was captured by the local sheriff. He was known at the time and popularised in the press as “the last wild Indian”.

He called himself “Ishi” – a word in the Yahi language that means simply “man”. He was the very last of his people, and had been living in the wilderness alone, travelling to places he remembered from the time when his tribe had flourished, in the hope of finding some remnant of those he’d grown up with. When he realised they were truly all gone, when a series of forest fires meant he was close to starvation, he allowed himself to be found and taken in.

Knowing that he …

Naiomi Alderman described the book as follows in the Guardian Newspaper; "On 29 August 1911, a 50-year-old man, a member of the Yahi group of the Native American Yana people, walked out of the forest near Oroville, California, and was captured by the local sheriff. He was known at the time and popularised in the press as “the last wild Indian”.

He called himself “Ishi” – a word in the Yahi language that means simply “man”. He was the very last of his people, and had been living in the wilderness alone, travelling to places he remembered from the time when his tribe had flourished, in the hope of finding some remnant of those he’d grown up with. When he realised they were truly all gone, when a series of forest fires meant he was close to starvation, he allowed himself to be found and taken in.

Knowing that he was the last surviving Yahi, Ishi was desperate to communicate some of the culture that would be entirely lost when he was gone. He ended up living with the director of the museum of anthropology at the University of California, Alfred Kroeber. He taught Kroeber as much as he could: demonstrated the skills of flint-knapping, explained his language, told the stories of his people one last time so they could be written down and preserved. He was particularly fond of children, Kroeber recorded. Ishi died in 1916, of tuberculosis. After his death, Alfred’s wife, Theodora, wrote a remarkable book about him, Ishi in Two Worlds, which relays as much of the Yahi culture as the anthropologists were able to record, and talks about Ishi’s own accounts of his life. To read it is to touch an intricate and beautiful civilisation that is now entirely gone, a place that can only be momentarily resurrected by an imaginative act, as unreachable as an alien world.