Hardcover, 324 pages

English language

Published Aug. 8, 2007 by Trafford Publishing.

Hardcover, 324 pages

English language

Published Aug. 8, 2007 by Trafford Publishing.

Review Written by Bernie Weisz, Vietnam War historian, July 30, 2010 Pembroke Pines, Florida contact: Bernwei1@aol.com

Title of review: "Triple Canopy Jungle, Red Dust Everywhere, Leeches, Scorpions, Tigers and the Best Jungle Fighters on Earth Shooting at You!"

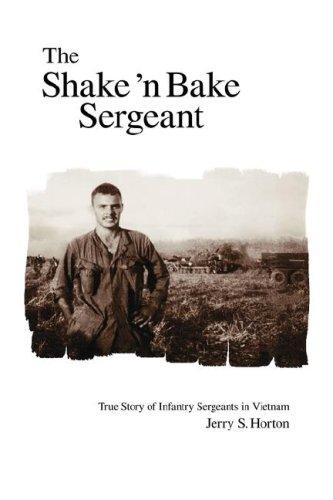

William Tecumseh Sherman, a Union General during the U.S. Civil War of 1861 to 1865 was quoted as saying: "There's many a boy here today that looks on war as all glory, but boys, it is all hell." In Jerry Horton's book "The Shake 'N Bake Sergeant", you will hear 140 years later a similar message, but a different war in a different situation and different continent. Mr. Horton is quoted as saying: "War is hard work, lousy food, no rest and occasional moments of utter terror." There were 3 main statistics Americans used for their own forces. The first one was "WIA" or "wounded in action." This meant a soldier had …

Review Written by Bernie Weisz, Vietnam War historian, July 30, 2010 Pembroke Pines, Florida contact: Bernwei1@aol.com

Title of review: "Triple Canopy Jungle, Red Dust Everywhere, Leeches, Scorpions, Tigers and the Best Jungle Fighters on Earth Shooting at You!"

William Tecumseh Sherman, a Union General during the U.S. Civil War of 1861 to 1865 was quoted as saying: "There's many a boy here today that looks on war as all glory, but boys, it is all hell." In Jerry Horton's book "The Shake 'N Bake Sergeant", you will hear 140 years later a similar message, but a different war in a different situation and different continent. Mr. Horton is quoted as saying: "War is hard work, lousy food, no rest and occasional moments of utter terror." There were 3 main statistics Americans used for their own forces. The first one was "WIA" or "wounded in action." This meant a soldier had incurred an injury due to an external agent or cause. The term encompassed all kinds of wounds and other injuries incurred in action, whether there was a piercing of the body, as in a penetration or perforated wound, or none, as in the contused wound. These included fractures, burns, blast concussions, all effects of biological and chemical warfare agents such as Agent Orange, and the effects of an exposure to ionizing radiation or any other destructive weapon or agent. The second was "Missing in Action/Prisoner of War" or "MIA/POW". This was used when an American soldier was lost and their whereabouts were unknown, but their death was not confirmed. When a soldier was designated as a P.O. W., he was presumed taken by or had surrendered to enemy North Vietnamese/Viet Cong forces. The third was "Killed In Action" or KIA. This was when an American military member was killed outright by enemy action or who died as a result of his/her wounds or other injuries before reaching a medical treatment facility. In "The Shake @ Bake Sergeant," Jerry Horton was a WIA, and came very close to the other 2 categories!

The Vietnam War was a Cold War military conflict that occurred in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia from November 1, 1955 and officially concluded on April 30, 1975 when Saigon (now Ho Chi Minh City) fell. This war followed the First Indochina War fought by the French and was funded by the Americans. It was fought between the Communist North Vietnam, supported by its communist allies, the Soviet Union and Red China. Opposing them were the "supposedly democratic" government of South Vietnam, supported by the United States and other anti-communist nations such as Australia, South Korea, Thailand and the Philippines. The Viet Cong, also known as the National Liberation Front (NLF) was an armed communist-controlled common front that was situated in the Southern part of Vietnam. For the most part, the VC fought a guerrilla war against the U.S. and South Vietnam's conscripted army, known as the Army Republic Of Vietnam, or ARVN for short. They also battled both the Australian/New Zealand contingent (known as "ANZAC" forces) and South Korean (referred to as "ROK) anti-communist troops. The North Vietnamese Army (referred to as "NVA") engaged in a more conventional war, at times committing large, well armed and uniformed units into at times "set piece" battles. U.S. and South Vietnamese forces relied on air superiority and overwhelming firepower to conduct search and destroy operations primarily involving ground forces, artillery and air strikes. America entered the conflict ostensibly to prevent a communist takeover of South Vietnam as part of their wider strategy of containment. Military advisors arrived beginning in 1950. Escalating in the early 1960's, U.S. troop levels tripled in 1961 and again in 1962. The "Gulf of Tonkin Resolution" was a joint resolution that the United States Congress passed on August 7, 1964 in response to a "supposed" sea battle that allegedly occurred between the NVA's Navy Torpedo Squadron and the destroyer USS Maddox on August 2, 1964, and an second naval engagement between NVA torpedo boats and the US destroyers USS Maddox and USS Turner Joy on August 4, 1964, in the Tonkin Gulf. The significance of the "Tonkin Gulf Resolution" was that it gave President Lyndon B. Johnson authorization without a formal declaration of war by Congress the use of conventional military force in Southeast Asia. Furthermore, it authorized the President to do whatever he deemed necessary to assist "any member or protocol state of the Southeast Asia Collective Defense Treaty" or (SEATO). This included involving armed forces.

U.S. combat units were deployed immediately following this resolution in 1965. Operations crossed borders, with Laos and Cambodia heavily bombed. Involvement peaked in 1968 at the time of the January "Tet Offensive." With mounting domestic bad publicity, climbing KIA figures, and anti-war "teach ins" on college campuses, U.S. involvement in Vietnam was doomed. The most powerful influence turning public opinion against the war was the media. Vietnam was the first televised or "living room" war. Each evening, the networks would show film of the fighting that was, at times, gruesome. Unlike the practice during World War II, the film was neither censored nor subject to any systematic scrutiny by the government. Americans were shown scenes of battles in progress, the dead and wounded, and the coffins of the dead being unloaded. One of the more shocking photographs of the war occurred during the TET offensive. A Viet Cong terrorist was captured by South Vietnamese military officials and summarily executed in the streets of Saigon. After this, U.S. ground forces were withdrawn as part of a policy called Vietnamization. Despite the Paris Peace Accords, signed by all parties in January 1973, fighting continued. The "Case-Church Amendment" was passed by the U.S. Congress prohibiting use of American military in Vietnam after August 15, 1973 unless the president secured congressional approval in advance. All American troops were withdrawn that year. The capture of Saigon by the North Vietnamese Army in April 1975 marked the end of the Vietnam War. North and South Vietnam were reunified the following year. However in human toll, the costs of this war was staggering. The Vietnam War killed 3 to 4 million Vietnamese from both sides, 1.5 to 2 million Laotians and Cambodians, and approximately 58,159 U.S. soldiers. Jerry Horton came very close to being one of them.

Jerry Horton's story is about his involvement as a member of an American Army unit called "A-1-8" (A company, 1st BATTALION, 8 TH INFANTRY) during his tour in Vietnam as well as his near fateful participation in the March, 1969 "Operation Wayne Grey." This operation saw his unit attempt to thwart the enemy in it's attempt to construct roads deep into the mountain range east of the Plei Trap Valley. This book is very similar in content to an unfortunately unavailable publication written by Danny M. Francis. In "Last Ride Home" Mr. Francis wrote from several different perspectives his near fatal participation in "Operation Harvest Moon" in December, 1965. What differs this book from Danny Francis's work as well as 99% of all other memoirs out there on the Vietnam War is the intricacies and subtle nuances that Mr. Horton brings to light rarely written about elsewhere. Jerry starts with his childhood in Charleston, West Virginia, his parents painful divorce, his attempt to break the "hillbilly label" of non achievement and unsophistication by attempting to attain a college degree in engineering, an accomplishment he proudly holds today. In fact, he actually holds a PhD in Electrical Engineering and currently is the President and founder of "Electrical Software Associates," an accomplishment he proudly shares with his readers. However, in September of 1966 he attended one year of college and then despite posting a 3.87 and 4.0 G.P.A. respectively, ran out of money, what he always called a "nagging concern." Dejected, he took the worst jobs, whereupon he lived on a tugboat that was tied to an offshore oil rig. His job consisted of hanging himself upside down beneath the rig suspended by ropes perilously using a high powered hose to do sandblasting as well as tossing 75 lb. bags of sand into a sandblasting hopper. Disenchanted, he quit and was attracted to California with it's 1967 "Summer of Love." Enamored with the hippie's philosophy of "doing anything he wanted to as long as he didn't hurt anyone" and "free love," Horton embarked to the "hippies' Mecca". With $100 he hitchhiked on Route 66 and landed in "hippie heaven" i.e. Haight Ashbury. Vividly recalling a Janis Joplin concert, going to "happenings" and Hell's Angel's parties, he spent 1 month there and decided to move on. Landing in Chicago, employed as a dreary "tar cleaner," he realized that the only way he would ever get back to college was on the G. I. Bill. Deciding to join the army, Horton wrote: "One day, covered in tar, I stood there in the middle of the room staring into space. I asked myself, "How can things get any worse? Then I screamed at the top of my lungs, "I give up, they can have me, take me." I made a desperate decision." This decision almost cost him, as the reader of this book will see, nearly his life on March 12, 1969 in South Vietnam's "Plei Trap Valley."

There are scores of memoirs currently out there that were written in mass abundance in the 1980's. Why did Jerry Horton decide to write this book nearly 39 years after his Vietnam experiences? After quitting a job that he was at the helm of for 15 continuous years, he mortgaged his house, started a basement run business, and after horrifyingly suffering the tragic drowning loss of a friend on a fishing trip, Horton decided he needed a break in the form of a vacation. Awaiting a three hour flight to Fort Myers, he purchased in an airport bookstore a book about the Army Special Forces in Vietnam. Coming across a passage written by Jesse Ventura, best known as Jesse "The Body" Ventura, Horton was infuriated. Ventura is an American politician, former governor of Minnesota, retired professional wrestler and color commentator, Navy UDT veteran, actor, and former radio and television talk show host. He is best known for his tenure in the World Wrestling Federation as a professional wrestler and color commentator. Horton wrote: "About 3/4 of the way through the book I came upon a startling passage written by Ventura: "A Shake 'n Bake Sergeant was one of the lesser known evils to come out of the Vietnam war and infect the army. These twerps would attend some NCO school (noncommissioned officer) school for 6 to 8 weeks and come out of it an E-5, buck sergeant, No experience, little skills, but a great big attitude". I read this passage again and again. Damn. Someone had actually written this for publication-and maybe millions to read-that I was an evil person and a twerp and that the Army had screwed up when it had promoted me to sergeant. I shut the book, closed my eyes, and thought about these stinging words for a moment. I was genuinely embarrassed. Then I got mad. I had been one of those Shake 'n Bakes. Was my experience in Vietnam a sham, an illusion? I had not thought about my tour in the Nam for 30 years. I had not talked about it with anyone. Now, my past was staring at me and awakening long forgotten and painful memories. At the time, many people had disliked us Shake 'n Bake sergeants. But was I really that bad? My vacation vanished from my thoughts and Vietnam emerged. My vacation was over before it started. A new journey had begun...a journey halfway around the world, and back in time. Back to the very beginning, it would not end until I had recovered my past as a Shake 'n Bake Sergeant in Vietnam." A "Shake n' Bake Sergeant" was a Vietnam War-era term for a young, non-commissioned officer of the United States Army who gained his stripes quickly through attending an NCO school with little actual time in the military. Jerry Horton goes through a painstaking discourse of the intensity of his training, his valued and admired leadership of his men, and his diligent concern for their welfare during his service in Vietnam. This led eventually to his earning two Silver Stars, an honor delayed until it was bestowed upon him in the year 2000.

However, Horton's book is much deeper than his justification of his leadership value as a "Shake 'n Bake" Sergeant or the details of the March 12, 1969 Plei Trap Valley" battle. In many respects, Horton's work is a scathing denouncement of the American war effort and involvement in S.E. Asia. He starts early in the book when he commented on his thoughts after being medically evacuated by helicopter from the Plei Trap Valley to a hospital ward, receiving life saving surgery. Knowing that his shrapnel wounds were "million dollar" (a million-dollar wound was military slang for a type of wound a soldier received in combat that was serious enough to get him sent away from the fighting, but wasn't fatal, nor permanently crippling) he mused to himself between comforting waves of morphine induced sedation the following ridiculous set of circumstances the U.S. Army sent "A Company" into battle under. Horton wrote: The Army kept us searching for the enemy for days on end, we were sent on the most dangerous and difficult missions. I remember Pappy grumbling, "they don't care about us. We're grunts. No one gives a damn." Flea said again "We gotta stick together. Why can't they give us some food? We are exhausted and filthy. Shea complained, "How can we fight without socks and water?" My men didn't want to fight anymore, they wanted to survive and go home. They wished to be sent to the rear, for at least a couple of weeks to rest. But there was nothing we could do about it. We were the U.S. Army grunts...some of the few thousand soldiers who did the actual fighting. The Army treated us like a pack of wild dogs, good for sniffing out the enemy and chasing the enemy over the Plei Trap. We had humped all day for weeks, with nothing but cold c-rations and rationed water. We dug in after dark every night, and then mounted constant ambushes until daybreak. I remembered looking at Jerry Loucks and saying "I wish we could just get it over with. Why can't we just soot it out and be done? That would be better than hunting them every day and getting shot at." My mind, my body, and my spirit were exhausted. It was no different for any of my men. How could I-how could my men-fight in this condition?" Certainly you will never find this type of information in a college level history book focusing on the failings of the American effort in Vietnam.

When Jerry Horton volunteered for the Army and Vietnam, he mistakenly thought his chances of winding up in combat were slim, at most. Citing statistics that there were over 400,000 troops in the rear units (referred to as "REMF's") supporting the 70,000 men fighting in the jungles, only 1 in 30 was placed in the unenviable position of being an NVA target. Jerry Horton wound up being the 1 out of 30! Deplaning at Cam Ranh Bay, Horton's comments set the stage for what was to follow. Lamenting, Horton quipped: "The heat was intense. Sweat rolled down my face and soaked my fatigues. The signs of war-trucks, tanks, planes and people-filled this vista. This was my new reality. I had entered the war zone." Never to be told in any history texts, Horton was given the impression immediately upon arriving in Vietnam that this war would never be brought to a successful conclusion. To this, Horton described: "I was told that if I encountered anyone in the jungle I could safely assume that they were the enemy. If they were not Americans and they carried weapons, I was instructed to shoot first and ask questions later. That is,if I wanted to live. The Ho Chi Minh trail was the Communist's main supply route from the North. The enemy moved both men and supplies down this trail on a daily basis. in our area of operations, the trail split into many small arteries on the Cambodian border. The U.S. Army was NEVER ALLOWED to follow the enemy into Northern Cambodia, to cut this enemy supply route. As a result, the enemy built a huge transportation system what was just out of our reach. They supplied the war, at will, with millions of tons of supplies and thousands of soldiers. Our operations could consist only of attacking enemy units that infiltrated South Vietnam, or that were based near the border, next to the Ho Chi Minh trail." American soldiers in Vietnam called home "the World" because Vietnam was not part of the real world. The World was where I would return when I left Vietnam. Until then, I was not part of any civilized society. I was in the Nam. The Nam was a unique society...a society of war. It was not part of our world. I would soon find out that the rules for operating in this society were different from any I had ever known." This certainly was both a different society and a war fought differently than any other. The NVA/VC were not the only enemy. Mr. Horton wrote of the fear out in "the bush" of a man eating lion, his lieutenant almost dying from a scorpion attack, a humorous story of where a medic had to detach a blood sucking leech that somehow lodged on a man's genitals, and the disgusting routine of burning human excrement, euphemistically referred to as "making soup." There is another story where one of Horton's fellow soldiers woke up in the middle of the night out of a dead slumber to find 2 NVA soldiers standing over him. This soldier fortunately had his M-16 rifle in his hands and killed both soldiers hovering over him instantly. Another peculiar story in this book involved the American practice of taking souvenirs from the dead. In one anecdote, Horton described where a fellow soldier took from a dead NVA a big large slab of ham that the deceased was carrying. Saving it for a special time to eat, he tried in vein to cut the packaging around "the ham" open. Noticing to his chagrin a red dot on the ham container, he realized for the past 48 hours he had been humping around a 2 lb. NVA land mine in his rucksack!

Other stories are sad reflections of this "forgotten war" that is only reminded by Americans with a wall in Washington D.C. and 58,109 names engraved upon it. Horton reminisced about his entry into Pleiku, a South Vietnamese city at the foot of mountainous jungles and at the end of the Ho Chi Minh trail as follows: "It was strange to see South Vietnamese peasants walking the road, trying to sell watches and cigarettes to the GI's driving by. They tried to sell boom boom, which was slang for sex. We passed through several small villages that seemed to be primarily whorehouses and bars. Most of the houses were made of mud and elephant grass. They smelled of rotten food, incense, spices and ginger. We noticed numerous Army trucks parked among these houses. South Vietnamese soldiers, who treated the trucks as their PERSONAL TRANSPORTATION, drove most of the vehicles. The whole city looked like one giant penny arcade. Never, in all my travels in the U.S. had I seen such a dirty place. People lived like rats. The houses were literally shacks stacked next to each other without any plan or organization. Fine red dust from the pulverized soil covered everything. The scene was like a movie from some faraway planet, but I wasn't watching it. I was in it!" Horton's description of fellow American GI's in Pleiku is incredulous and memorable: "We passed several army truckloads of American soldiers, crammed full with gear, rifles and ammunition. The men were all a dirty brown color and had a wild look I will never forget. They looked paranoid, wild, dirty, and dangerous, like people you would not want to mess with. I was amazed to find American soldiers looking like this. I could not believe American troops could be wild animals, As we passed they just stared directly at me, as though I were nothing but a piece of meat." With the aforementioned description, it is easy to understand how troops under Lieutenant William Cally could be involved in the infamous "My Lai Massacre" and less comprehensible how American troops could win the "Hearts and Minds" of the South Vietnamese population. "Hearts and Minds" was a euphemism for a campaign by the U.S. military designed to win the popular support of the Vietnamese people. "Hearts and Minds" campaigns typically referred to Liberal, Western governments that attempted to liberate oppressed people from communism, fascism or religious theocracies. However, when South Vietnamese people lived in fear of American troops as Horton described, it is unlikely they would allow American troops to protect them and help them rebuild schools and their infrastructure so that their allegiance could be pried away from the NVA/VC.

Sergeant Horton learned just how pernicious Vietnam truly was on his first helicopter ride. Being choppered from "Dak To" to a fire base upon "Hill 1049", he commented as he watched out the door gunner's bay the following: "Now I got to see the real Vietnam. These big mountains-thick with vegetation-were uncompromising and dangerous. The enemy could hide for A THOUSAND YEARS AND REMAIN UNDETECTED. I compared these mountains to those in West Virginia and California. I was in awe. For a moment, I thought, "How Beautiful"! Then...HOW DEADLY!" Jerry Horton saw that America's endeavors in Vietnam consisted of a 9 to 5 PM war. However, Horton responded: "The NVA liked to attack during the night when the rest of the world was sleeping. That's when they invaded villages, intimidated or killed the residents and stole their food and supplies. They disappeared into the jungle hideaways before daylight." "Fragging" became an issue late in the war.This referred to the act of attacking a superior officer in one's chain of command with the intent to kill him. The term was most commonly used to mean the assassination of an unpopular officer of one's own fighting unit by means of a fragmentation grenade, thus the term "fragging." The most common motive was a desire to avoid identification and punishment. Unlike a gun, an exploded hand grenade couldn't be readily traced to anyone by using ballistics forensics or by any other means because the grenade itself was destroyed in the explosion, and the characteristics of the remaining shrapnel weren't distinctive enough to permit tracing to a specific grenade or soldier. Why didn't Horton have to worry about this? Horton explained as such: "While learning the ropes (about Vietnam), I let the old timers look out for me. Above all, I didn't do anything stupid. I just took care of business and kept everyone alive. The men didn't want to be heroes. They just wanted to get back home. I understood this line of reasoning. Beyond that, the golden rules were simple:Don't ask anyone to do something I wouldn't do. Always put the welfare of my men first. My number one priority was for everyone to come home in one piece." There are comments that Jerry Horton made in this book that speak volumes. After walking 15 miles in two days with no socks on nor food and water, Horton remarked: "I'm going to teach my kids to hate the army and hate war. It is the most disgusting thing a person can go through and none of my kids are ever going to experience it."

Lieutenant Horton made enlightening comments in this book in regards to his participation in "Operation Wayne Gray" and the callousness of his superiors as far as his men's plight. As such, Horton wrote: "We were on constant patrol hunting for the enemy. It was a deadly cat and mouse game, Sometimes they were the mice and sometimes we were. We both understood the game, Be quick. Don't hesitate, or today might be your last. We were involved in another game, too. We were the pawns of the Brass: the generals, the colonels, and the majors. When they said, Move my pawn over there," it meant an all day hump for us grunts. Our lives were at risk, not theirs. Our endurance was being tested, not theirs. Our successes would earn us another day to live. Another day to dig another foxhole." Right before his near fatal encounter with the NVA at the Plei Valley Trap, Mr. Horton wrote a letter home which was included in this book. It's importance in terms of treatment and morale of American soldiers in Vietnam cannot be understated. Horton penned the following: "I was tired of the Army and tired of war. The way they kept us searching for the enemy for a fight, I knew we were going to get it-probably a big one. The men didn't want to fight any more. They wanted to survive and go home. But there was nothing we could do about it. it was going to happen; I could feel it. Maybe this time the bullets wouldn't just whiz by me, like they did when Cheek got shot. If that was what it would come to, then I was ready no matter what. The Army was treating us like a pack of wild dogs, sniffing out the enemy, and chasing the NVA all over the Plei Trap. We humped all day on C-rats and rationed water, dug in after dark, then had to mount constant patrols or watches during the night. I was tired of it. I wanted to find the enemy, have a shoot out and get it over with. I was tired about worrying about it. My mind, my body and my spirit were exhausted. How could I expect to fight for my life in this condition? We were truly, truly animals now. That's all we were worth to the Army. At least if I died, I would be treated like a person." How could this nation expect our forces to be victorious in Vietnam under those conditions? It is very hard to read Jerry Horton's account of what happened on March 12, 1969 with the knowledge of the mind set he and his men went into battle with on that fateful day. Finally, Jerry Horton ended this amazing book with the following passage he wrote about on March 26, 1969. Laying in the 249th Army Hospital bed in Osaka, Japan, awaiting his flight to Walter Reed Army Hospital in Washington, D.C., he wrote: "I realized I would have to start over. Nam was the price I had paid to get to go to college. My life would never be the same. I had used my skills to become a Shake 'n Bake sergeant in the Vietnam war. I had done my best. The little boy who had loved to play with his plastic toy soldiers and to draw pictures of warriors had become one. Now this boy couldn't stand war. Now this boy couldn't stand war. The thought of it made him sick to his stomach. Silently, I cried in my hospital bed. I didn't want anyone to hear me. Soldiers weren't supposed to cry."