Paperback

Published 2019

Paperback

Published 2019

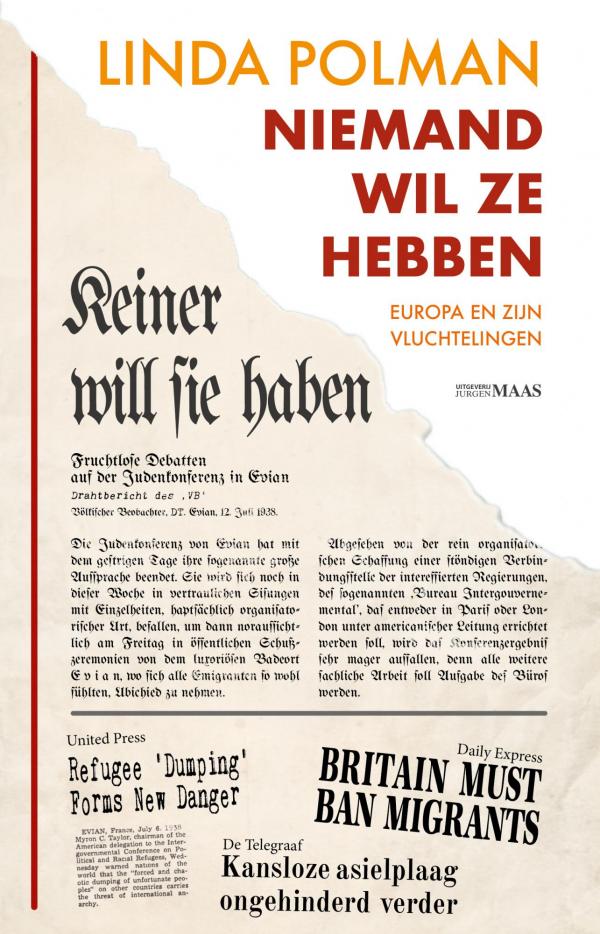

This story about European 'refugee management' starts in the summer of 1938 in the stately French spa town of Evian, at the first international summit about the refugee crisis in Europe. The number of Jews who tried to escape from the Nazi occupied territorium had exploded: reception places were needed urgently. All Western European countries were present at Evian and their arguments for not letting in the refugees were the same as now: the 'migrants' would not be compatible with national norms and values, would take jobs and houses and would be a threaten for societal cohesion.

The only thing the conference produced was the scorn of Nazi Germany: despite all criticism of human rights violations in Germany, none of the 'civilized' countries had shown their willingness to save the Jews. 'No one wants to have them', a German newspaper triumphantly triumphed when the deputies returned home from Evian.

…This story about European 'refugee management' starts in the summer of 1938 in the stately French spa town of Evian, at the first international summit about the refugee crisis in Europe. The number of Jews who tried to escape from the Nazi occupied territorium had exploded: reception places were needed urgently. All Western European countries were present at Evian and their arguments for not letting in the refugees were the same as now: the 'migrants' would not be compatible with national norms and values, would take jobs and houses and would be a threaten for societal cohesion.

The only thing the conference produced was the scorn of Nazi Germany: despite all criticism of human rights violations in Germany, none of the 'civilized' countries had shown their willingness to save the Jews. 'No one wants to have them', a German newspaper triumphantly triumphed when the deputies returned home from Evian.

Journalist Linda Polman describes the development of the strategy in Europe's refugee policy since 1938. Drawing on her own research, experiences and conversations, she takes the reader on a voyage starting at Evian, over the post-war camps in Western Europe for refugees fled from behind the Iron Curtain and the 'safe enclaves' for refugees in the Balkans in the 1990s, to the dozens of Europe-funded UNHCR refugee camps now in Africa. She outlines, among other things, the stranglehold that Europe has on the UNHCR. The UN organization, which has to stand up for the rights of millions of refugees around the world, is financially wholly dependent on European donor governments and is therefore subject to Europe's whims.

The trip ends in the Greek Lesbos, the epicenter of the largest European refugee crisis since 1938. The arrival in 2015 of more than one million refugees to the EU could be predicted well in advance, but European politics did nothing to prepare their reception. Consequences were chaos and election profits for right-wing extremist movements.

Linda Polman examines the question of what has come of the promise of 'never again' on which the UN refugee treaty was based in 1951. Europe has even "accepted death as an effective anti-migration instrument," the United Nations Human Rights Council ruled in 2018.

Eighty years of European 'refugee management' and still no one wants them.