fountainhead wants to read Mirror & the Light by Hilary Mantel

Mirror & the Light by Hilary Mantel

‘If you cannot speak truth at a beheading, when can you speak it?’

England, May 1536. Anne Boleyn is dead, …

“You do not need to leave your room. Remain sitting at your table and listen. Do not even listen, simply wait. Do not even wait, be quiet still and solitary. The world will freely offer itself to you to be unmasked, it has no choice, it will roll in ecstasy at your feet.”

– Franz Kafka

This link opens in a pop-up window

‘If you cannot speak truth at a beheading, when can you speak it?’

England, May 1536. Anne Boleyn is dead, …

Earlier versions of most of these essays first appeared in Details, Graywolf Forum, Harper's, and The New Yorker. The essay …

We hear it all the time: “Sorry, it was just an accident.” And we’ve been deeply conditioned to just accept …

One of the great masterworks of science fiction, the Foundation novels of Isaac Asimov are unsurpassed for their unique blend …

New York Times bestseller Cory Doctorow's Red Team Blues is a grabby next-Tuesday thriller about cryptocurrency shenanigans that will awaken …

In this exhilarating novel by the best-selling author of The Storied Life of A. J. Fikry two friends—often in love, …

He found himself uttering a series of "excuse mes" that he did not mean. A truly magnificent thing about the way the brain was coded, Sam thought, was that it could say "Excuse me" while meaning "Screw you." Unless they were unreliable or clearly established as lunatics or scoundrels, characters in novels, movies, and games were meant to be taken at face value-the totality of what they did or what they said. But people-the ordinary, the decent and basically honest-couldn't get through the day without that one indispensable bit of programming that allowed you to say one thing and mean, feel, even do, another.

— Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow by Gabrielle Zevin (Page 4)

Spot on.

Sam didn't care for crowds -- being in them, or whatever foolishness they tended to enjoy en masse.

— Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow by Gabrielle Zevin (Page 3)

I feel you.

In this exhilarating novel by the best-selling author of The Storied Life of A. J. Fikry two friends—often in love, …

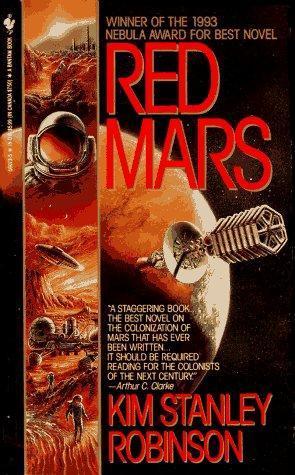

"[...] When we first arrived, and for twenty years after that, Mars was like Antarctica but even purer.We were outside the world, we didn't even own things-some clothes, a lectern, and that was it! Now you know what I think, John. This arrangement resembles the prehistoric way to live, and it therefore feels right to us, because our brains recognize it from three millions of yearspracticing it. In essence our brains grew to their current configuration in response to the realities of that life. So as a result people grow powerfully attached to that kind of life, when they get the chance to live it. It allows you to concentrate your attention on the real work, which means everything that is done to stay alive, or make things, or satisfy one's curiosity, or play. That is utopia, John, especially for primitives and scientists, which is to say everybody. So a scientific research station is actually a little model of prehistoric utopia, carved out of the transnational money economy by clever primates who want to live well." "You'd think everyone would join," John said. "Yes, and they might, but it isn't being offered to them. And that means it wasn't a true utopia. We clever primate scientists were willing to carve out islands for ourselves, rather than work to create such conditions for everyone. And so in reality, the islands are part of the transnational order. They are paid for, they are never truly free, there is never a case of truly pure research. Because the people who pay for the scientist islands will eventually want a return on their investment. And now we are entering that time. A return is being demanded for our island. We were not doing pure research, you see, but applied research. And with the discovery of strategic metals the application has become clear. And so it all comes back, and we have a return of ownership, and prices, and wages. The whole profit system. The little scientific station is being turned into a mine, with the usual mining attitude toward the land over the treasure. And the scientists are being asked, What you do, how much is it worth? They are being asked to do their work for pay, and the profit of their work is to be given over to the owners of the businesses they are suddenly working for." "I don't work for anyone," John said.

"Well, but you work on the terraforming project, and who pays for that?"

John tried out Sax's answer: "The sun."

Arkady hooted. "Wrong! It's not just the sun and some robots, it's human time, a lot of it. And those humans have to eat and so on. And so someone is providing for them, for us, because we have not bothered to set up a life where we provide for ourselves."

John frowned. "Well, in the beginning we had to have the help. That was billions of dollars of equipment flown up here. Lots of work time, like you say."

"Yes, it's true. But once we arrived we could have focused all our efforts on making ourselves self-sufficient and independent, and then paid them back and been done with them. But we didn't, and now the loan sharks are here. [...]"

— Red Mars by Kim Stanley Robinson, Kim Stanley Robinson (Mars (1)) (Page 342)

Arkady talks to John about how society on Mars is changing.

"But that's already true," John said. "How is this different from the economics that already exists?"

They all scoffed at once, Marina most persistently:

there's all kinds of phantom work! Unreal values assigned to most of the jobs on Earth! The entire transnational executive class does nothing a computer couldn't do, and there are whole categories of parasitical jobs that add nothing to the system by an ecologic accounting. Advertising, stock brokerage, the whole apparatus for making money only from the manipulation of money -- that is not only wasteful but corrupting, as all meaningful money values get distorted in such manipulation." She waved a hand in disgust.

— Red Mars by Kim Stanley Robinson, Kim Stanley Robinson (Mars (1)) (Page 299)

Anyway that's a large part of what economics is people arbitrarily, or as a matter of taste, assigning numerical values to non-numerical things. And then pretending that they haven't just made the numbers up, which they have. Economics is like astrology in that sense, except that economics serves to justify the current power structure, and so it has a lot of fervent believers among the powerful.

— Red Mars by Kim Stanley Robinson, Kim Stanley Robinson (Mars (1)) (Page 297)