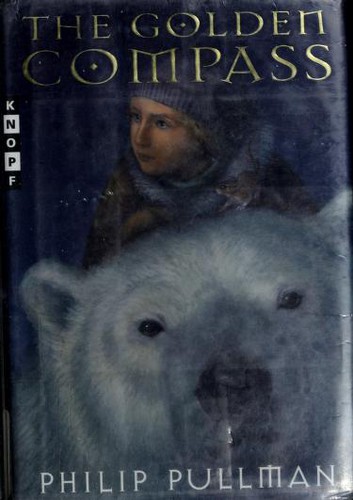

emfiliane reviewed The Golden Compass by Philip Pullman

Review of 'The Golden Compass' on 'Goodreads'

5 stars

This ripping yarn of a Victorian fantasy almost appears to be a fusion of C.S. Lewis and Jules Verne, but the story is uniquely Pullman's. The writing was strong enough that I was drawn completely in within the first few pages, given no chance to set it down for long.

The young woman Lyra is thrown into political intrigue from the moment the story starts, and her travels from Oxford College to London to the great snowy north parallel her growth from young girl to an adult, and she emerges from being a pawn in others' designs to taking control of her own destiny and others'. As we follow her, the dazzling world slowly unfolds around us, in thoughts, memories, and dialogue, rather than expository infodumps. In large part the reader is left on her own to figure out what's going on and why, given hints and pushes; we are whirled along with Lyra, barely a moment given to see into other people, and the story is significantly stronger for it.

This book never stops moving. That is probably the most addicting part of it; no matter where you stop, there's always something peeking right around the corner that makes you have to come back just as quickly as possible. At the same time, it's too fast for a single sitting; you just have to take a breather here and there to let things settle in your mind. There are many fascinating threads here, tied together in a world very like our late-19th century England. Daemons that are almost a physical manefestation of the soul; armored bears who are barbaric knights; a gizmo that speaks knowledge; the Aurora with the strange city inside it; and the mysterious Dust that everyone is so interested in. Yet it is all handled deftly, with easy aplomb. Even the more fantastic events and items turn out to have believable and grounded histories.

Unlike the sequel, the religious aspect of the story is buried beneath the characters themselves. Mrs. Coulter's connection to the Church is often mentioned, but never really showing how it affects others except indirectly. To Coulter, is it simply a vehicle to power, or is it a deeper faith that coincides with her ambitions? Instead, it focuses mainly on the external spirits as a visible soul: Children whose daemons are malleable and chaotic, adults' that are more fixed and sturdy; just the idea of being without it is horrifying to anyone. Thus the plot twist is pretty easy to see. Witches can send their daemons much further than others, and they are thus more autonomous. Then you have the bears, whose armor is practically their soul; they can make more if they have to, unlike humans. When people are seen without souls, mentally enfeebled or apathetic, it becomes the subject of a bit of overdone philosophizing, though.

Highly recommended to anyone with an imagination and sense of wonder. This is something that will be as fresh and wonderful every time you read.