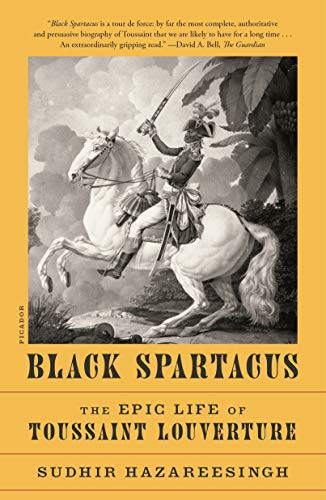

"In overthrowing me, you have cut down in San Domingo only the trunk of the tree of liberty. It will spring up again by the roots for they are numerous and deep." C.L.R James describes these words as the "last legacy" Toussaint L'Ouverture gave his compatriots as the French Navy whisked him away to Europe as a political prisoner. Spoken in 1802 near the conclusion of a more than decade long, brutally violent civil and revolutionary war, James dramatically recites them as a coda for his own revolutionary struggle for Black freedom from the imperialists in Europe and America.

James, a scholar and author from Trinidad, wrote The Black Jacobins as a radical reclamation of the struggle for freedom in Haiti. The book consciously situates itself in a Marxist-Trotskyist historical drama; the author clearly points out where revolutionaries and counter-revolutionaries at the close of the 18th century resemble those of the beginning of the 20th. Consider this passage from chapter 8, "The White Slave Owners"

"""

Robespierre and the Mountain had maintained power until July 1794. The Terror has saved France, but long before July Robespierre had gone far enough and was now lagging behind the revolutionary masses. In the streets of Paris, Jacques Varlet and Roux were preaching Communism; not in production but in distribution, a natural reaction to the profiteering of the new bourgeoisie. Robespierre, however, revolutionary as he was, remained bourgeoisie and had reached the extreme limit of bourgeoisie revolution. He persecuted the workers -- far more working-men than aristocrats perished in this phase of the Terror. In June 1794, the revolutionary armies won a great victory in Belgium; and at once the continuation of the terror was seen by the public as factional ferocity and not a revolutionary necessity .....

The tragedy was that the Paris masses, in leaving him to his fate, were opening the door to worse enemies. Robespierre's successors were the new officialdom, the financial speculators, the buyers of church property, all the new bourgeoisie. The were enemies of royalty ... but were determined to keep the masses in their place and willing to ally themselves with the old bourgeoisie, and even some of the aristocracy, in a joint exploitation of the new opportunities created by the revolution .... reaction increased, and as it grew the old slaveowners, crawling out of their prisons and hiding-places, held up their heads again and clamored for 'order' to be restored in San Domingo and the colonies.

"""

Entire books can be written on just the episode James highlights here, but his stirring summary has a determined purpose for his audience. First, there's a historico-logical progression of events, from revolutionary fervor to reactionary response and back to simmering discontent. This formulation comes from Marx; compare James' presentation of events with Marx' own theoretical perspective, particularly in the essay "The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte." It's not difficult to see that the worst of the "worse enemies" alluded to in the passage is Napoleon Bonaparte, who would seize power as First Consul of the French Republic in 1798 and soon initiate a war in San Domingo to re-institute slavery.

But second, and more importantly for appreciating C.L.R. James as an author, historian, and revolutionary in his own right, this passage intends for his readers to see how they, too, have been double-crossed by their own power-hungry contemporaries. James wrote the first edition in 1938 -- shortly after Stalin consolidated power in the Soviet Union, Hitler threatened all of Europe, and Franco destroyed the remnants of the Spanish revolution. That same year Leon Trotsky established the Fourth International, denouncing Stalinism and calling for "permanent revolution." For his part, as a black man from British controlled Trinidad, this meant finally freeing the Caribbean, Americas, and Africa from colonial forces and influences. It's hard for us to appreciate now, but the Pan-African movement, for James, was as much a anti-colonial struggle as it was a proletariat struggle, with all the racism that was (and still is) embedded in the relationship between European and non-European revolutionaries.

In short, the double-speak from France regarding its colonies was no worse in 1798 than in 1938. A generation and much bloodshed later, in 1960 for the second edition, James would find little to change in his presentation, save a few minor edits to make the text more contemporaneous. Of course, as that second edition went to print, the remaining French colonies went to war yet again, in Algeria and in Vietnam. Only 34 years since James' passing, it's hard not to read this book with some trepidation, and hope, for continued efforts towards a more free world.

I'll close this review with another quote, this time from David Scott's introduction in the 2023 reprint: "[James] means that Toussaint was literally unprecedented, unparalleled, not simply in the sense that he had no equal, but in the strict sense that he was original, singular, a hitherto inconceivable form of human life. As everyone who reads the book will immediately recognize, James' Toussain was not simply an ordinary figure of remote and provincial local knowledge; he was the larger-than-life figure of a heroic world-historical universality. He was a man who, while completely shaped by the constraining particularities of his degraded, enslaved circumstances, was nevertheless not reducible to them."

We surely could use more leaders like Toussaint L'Ouveture and more writers like C.R.L James today.