Warning: Extremely Vague Spoilers

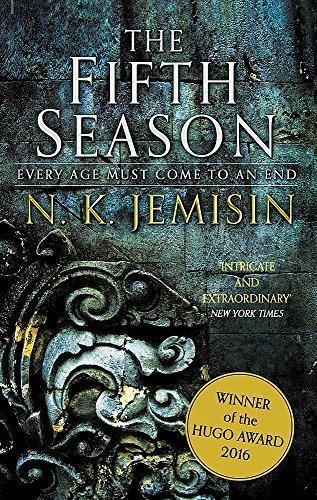

It’s clear to see why The Fifth Season won a Hugo award and became immensely popular. Jemisin is an amazing world-builder and extremely good at plotting. She knows exactly at what pace to reveal the mysteries of her world to make her readers desperate to find out what happens next. The culture and history of her world are shaped by the titular “fifth seasons” years-long periods of environmental disasters, which is a great concept, and her orogenes are a really cool half-magic, half-science twist on typical elemental magics.

She also manages to do something that was once thought impossible: create fantasy-cursing that sounds both thematic and natural.

Jemisin wants to do more than just write an exciting book though, she has a message, a two-fold one at that. She’s clearly both inspired by climate disasters in our world, as well as (racial) oppression. I say racial, because while the orogenes aren’t a one-on-one for an actual real-life group, there’s hints (like the slightly-on-the-nose slur for them being “rogga”) that she was inspired by the oppression of Black people. There’s nothing wrong with that, in fact, I’m always happy when an SFF author sees the potential in their fictional world to dissect and analyze our real world. I think especially fantasy is deeply underutilized in that respect. However, I am disappointed in how she went about it. While I’m fully aware how white and arrogant this sounds; I think she could’ve done better.

A review on Goodreads, by Nick Imrie, really put it better than I could “…I can't help but feel that the rape, torture, slavery and abuse are all set-dressing, while the real visceral oppression is here in the social snubs, slights and slurs. In the world of The Fifth Season rape is quotidien but being called rogga is unforgivable.”

Harsh, but I think she really managed to identify what bothered me so much about her treatment of oppression in this book. It seems like the most visceral feeling moments of cruelty and bigotry are the ones she’s actually likely to have experienced herself, rather than the ones that are actually the worst.

The orogene characters in this book do terrible things, they kill people accidentally and on purpose, allies and enemies, sometimes one, sometimes many. The guilt they experience over this is minimal, and often they halfway justify it by making the argument that the people they killed all contributed to the oppressive system under which orogenes are forced to live (which, admittedly, is truly horrific). Jemisin seems to agree. I get the sense that we’re supposed to see this world as irredeemable because of the bigotry and cruelty of its inhabitants.

And I understand that part of the genre conventions of these types of books is that Life is Cheap, but if you’re trying to make a point about oppression, it’s hard for me take it both ways. I can’t both sympathize with a character’s anger over being called a slur, ignore their comparative stoicism over being cast out from their family, and then excuse them semi-accidentally on purpose wiping out an entire village. The actions in this book aren’t afforded their proper emotional weight, in my opinion.

Within the logic of the world she created, orogenes have demi-god levels of power and are fully capable of accidentally killing people, even as infants. They are also undeniably people, despite their danger, but it’s easily understandable why regular folk would hate and fear them.

Now, as I said, Jemisin is an amazing plotter. I have no doubt she realized this, and already has an answer in store, (I’ve read the first fifty pages of the second book, and I’m placing my bets on “ancient indigenous knowledge on orogenes that was lost during Sanzed colonialism”) which disappoints me a little.

It feels pretty cliché to compare her to Octavia Butler, the only other Black female sci-fi author people are likely to have heard of, but it was one of her greatest strengths as a writer that she always fully engaged with these types of moral dilemmas. She never let her characters take the easy way out and discover some kind of ancient, lost third option. I just don’t trust Jemisin to do the same. (Though I’m prepared for her to embarrass me on this front. I have underestimated her before.)

I feel like Jemisin wants to use this book to pose us a question, except she has already scribbled in the answer. She wants to portray morally gray characters, but we never actually doubt who she considers “the good guys”. And she seems to be unable to go beyond her own experiences to truly confront the horrors of the world she created.

And that’s what could have taken this book from “good” to “great”, in my opinion. And, in all honesty, if this wasn’t a Hugo winner, I wouldn’t have scrutinized it to this extent. For me, it became a victim of its own high expectations.

So, conclusion.

Should you read this book? Honestly, yes.

Am I going to read the rest of the series? Yes, I need to know how this ends.

Am I bit disappointed? … Yeah, sadly.